Price and stock to confirm

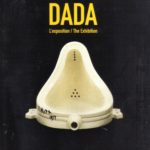

Editions du Centre Pompidou, 2005. Size 27 x 27 cm. ENGLISH-FRENCH Edition. With 80 reproductions in color and black and white on paper illustration. State: Used, excellent. 60 pages

What, then, does DADA mean? The tail of a sacred cow for the Kroo tribe; a word used in certain parts of Italy for a mother or a cube, and an Italian infant`s word for horse, as in gee-gee; a rocking horse; a nanny; a double affirmative in Slavic countries, and above all the first syllables uttered by many a baby, the primary phase of talking, and babbling as an assault on logic. These are some of the official definitions of this odd word adopted by a group of Zurich-based artists on 18 April 1916, found quite by chance by thrusting a knife-blade into a dictionary to find a pseudonym. A name that could be sufficiently freely interpreted to be thoroughly international, pushing any serious historical and intellectual reasons to one side. In 1918, in the third issue of the magazine DADA, Tristan Tzara came up with the bes definition: «DADA does not mean anything».

What, then, does DADA mean? The tail of a sacred cow for the Kroo tribe; a word used in certain parts of Italy for a mother or a cube, and an Italian infant`s word for horse, as in gee-gee; a rocking horse; a nanny; a double affirmative in Slavic countries, and above all the first syllables uttered by many a baby, the primary phase of talking, and babbling as an assault on logic. These are some of the official definitions of this odd word adopted by a group of Zurich-based artists on 18 April 1916, found quite by chance by thrusting a knife-blade into a dictionary to find a pseudonym. A name that could be sufficiently freely interpreted to be thoroughly international, pushing any serious historical and intellectual reasons to one side. In 1918, in the third issue of the magazine DADA, Tristan Tzara came up with the bes definition: «DADA does not mean anything».

DADA was the illegitimate child of a dirty war, the Great War, so called, which people thought would be so short and so effective. This technological war (mustard gas, Big Bertha, aerial dogfights) was not meant to last beyond the summer of 1914, but it went on for four years and chalked up nine million victims and casualties. DADA came into being out of the despair and disgust that reigned among the young people whom the military powers-that-be had not dispatched to the front. This was the political and aesthetic context from which the many-facetted expressions of Dadaism emerged in the Swiss cradle of Zurich, an island of neutrality amid a Europe put to fire and sword.

1916. Wounded and disabled war veterans were returning from the front in ever greater numbers. The war was becoming bogged down in the quagmire of Verdun. Blind good will was running out of steam, hope was fading, and there was the rumble of mutiny, which was systematically and bloodily put down. The disgust felt by intellectuals was swelling and leaking out in writings penned from their land of exile: Switzerland. It was in Zurich, a refuge of personalities as disparate as Hermann Hesse, Carl Jung and Vladimir Ulyanov Lenin, that a group of young artists, most of them in their early twenties, got together to rail, write, and disseminate their hatred and rejection of military blindness. The Alsatian artist Jean Arp, the Romanians Tristan Tzara and Marcel Janco, students of philosophy and architecture respectively, the German writers Hugo Ball, Emmy Hemmings, and Richard Huelsenbeck, the Dutch couple formed by Otto and Adya von Rees, and the Swiss artist Sophie Taeuber started to meet in a Zurich tavern from 5 february 1916 on, soon to be joined by two other artists, Hans Richter and Christian Schad. From this tavern they sent out a «mental alarm signal against the decline of values» (Janco).

1916. Wounded and disabled war veterans were returning from the front in ever greater numbers. The war was becoming bogged down in the quagmire of Verdun. Blind good will was running out of steam, hope was fading, and there was the rumble of mutiny, which was systematically and bloodily put down. The disgust felt by intellectuals was swelling and leaking out in writings penned from their land of exile: Switzerland. It was in Zurich, a refuge of personalities as disparate as Hermann Hesse, Carl Jung and Vladimir Ulyanov Lenin, that a group of young artists, most of them in their early twenties, got together to rail, write, and disseminate their hatred and rejection of military blindness. The Alsatian artist Jean Arp, the Romanians Tristan Tzara and Marcel Janco, students of philosophy and architecture respectively, the German writers Hugo Ball, Emmy Hemmings, and Richard Huelsenbeck, the Dutch couple formed by Otto and Adya von Rees, and the Swiss artist Sophie Taeuber started to meet in a Zurich tavern from 5 february 1916 on, soon to be joined by two other artists, Hans Richter and Christian Schad. From this tavern they sent out a «mental alarm signal against the decline of values» (Janco).

While a considerable number of Futurists and Expressionists were decimated at the front, a new movement sprouted among those young people whom the army had usually preferred to exempt from military duty, or declare unfit for service. The tavern turned into the Cabaret Voltaire -a homage to the French thinker who disagreed with royal policy and went into exile at ferney in Switzerland from 1758 to 1778- and boasted a stage and an audience for the fiery and iconoclastic evening shows put on by the cosmopolitan group which would soon be calling itself «DADA». «We were beside ourselves over the sufferings and debasement of humanity», wrote Marcel Janco. This gust of revolt went hand in hand with a desire and a need to make a clean break with a pictorial and literary tradition deemed bourgeois. Not to good taste, not to meaning, no to narrative, no to style, and no to war: DADA had no intention of lolling about; rather, it would rise up and rebel. In the initial phase, the written word and performances would be their favourite language, well before they turned to the visual arts.

While a considerable number of Futurists and Expressionists were decimated at the front, a new movement sprouted among those young people whom the army had usually preferred to exempt from military duty, or declare unfit for service. The tavern turned into the Cabaret Voltaire -a homage to the French thinker who disagreed with royal policy and went into exile at ferney in Switzerland from 1758 to 1778- and boasted a stage and an audience for the fiery and iconoclastic evening shows put on by the cosmopolitan group which would soon be calling itself «DADA». «We were beside ourselves over the sufferings and debasement of humanity», wrote Marcel Janco. This gust of revolt went hand in hand with a desire and a need to make a clean break with a pictorial and literary tradition deemed bourgeois. Not to good taste, not to meaning, no to narrative, no to style, and no to war: DADA had no intention of lolling about; rather, it would rise up and rebel. In the initial phase, the written word and performances would be their favourite language, well before they turned to the visual arts.

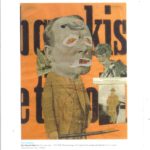

The acme of Zurich Dada tallied oddly with the departure of some of its members, starting with Richard Huelsenbeck who, in 1917, returned to a lifeless Berlin, famished by the blockade, and totally disheartened. The populace cast hopeful glances at the example of the Bolshevik revolution under way to the east. In the midst of mutinies, strikes, and Spartacist uprisings spurred on by Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, Richard Huelsenbeck and Raoul Hausmann felt a need to act, and do something. In April 1918, they founded a markedly anarchist DADA club, supported by the enthusiasm of George Grosz, John Heartfield, Hannah Höch and Johannes Baader. «There’s a difference between sitting quietly in Switzerland and lying on top of a volcano, the way we did in Berlin» (Richard Huelsenbeck). The Kaiser’s government suffered the onslaughts of the young group, whose aim was «to open the eyes of the people». Borrowing the principle of those bygone stormy evenings in Switzerland, the club nevertheless bore in mind the power of manifestos and produced them in large quantities. DADA was read and flaunted, and went looking for scandal which the press reported with much relish.

The acme of Zurich Dada tallied oddly with the departure of some of its members, starting with Richard Huelsenbeck who, in 1917, returned to a lifeless Berlin, famished by the blockade, and totally disheartened. The populace cast hopeful glances at the example of the Bolshevik revolution under way to the east. In the midst of mutinies, strikes, and Spartacist uprisings spurred on by Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, Richard Huelsenbeck and Raoul Hausmann felt a need to act, and do something. In April 1918, they founded a markedly anarchist DADA club, supported by the enthusiasm of George Grosz, John Heartfield, Hannah Höch and Johannes Baader. «There’s a difference between sitting quietly in Switzerland and lying on top of a volcano, the way we did in Berlin» (Richard Huelsenbeck). The Kaiser’s government suffered the onslaughts of the young group, whose aim was «to open the eyes of the people». Borrowing the principle of those bygone stormy evenings in Switzerland, the club nevertheless bore in mind the power of manifestos and produced them in large quantities. DADA was read and flaunted, and went looking for scandal which the press reported with much relish.

All the Dadaists assumed megalomaniacal nicknames: Hausmann was «dadasophe», Grosz was «Marschall» or «Propaganda». Heartfield was «Monteur Dada» (Dada Fitter) and Johannes Baader was «Oberdada», the gruop’s senior member. Just like Zurich Dada, this Berlin-based DADA would be pretty shortlived. The first International DADA Art Fair, held in 1920, already sounded the death knell for a movement whose individual advocates would never yield to the humility of the collective group. Hausmann duly joined Kurt Schwitters, the sole member of a DADA group set up in Hanover in 1920 (after having unsuccessfully applied to the Berlin committee), while another group came to the fore in Cologne, led by Max Ernst and Johannes Baargeld. Dubbed since 1918 by Jean Arp, the group turned out to be no less ephemeral, because it collapsed in 1921. Its brief period of provocative, bothersome, creative activity was a flamboyant one, staked out by many a magazine. Among them, Die Schammade proclaimed by way of the subtitle: «Dilettantes, rise up!». Its members gradually joined the Parisian movement spawned by the magazine Littérature, created in 1919 as a brainchild of André Breton, who gathered the writers Louis Aragon and Philippe Soupault around him.

All the Dadaists assumed megalomaniacal nicknames: Hausmann was «dadasophe», Grosz was «Marschall» or «Propaganda». Heartfield was «Monteur Dada» (Dada Fitter) and Johannes Baader was «Oberdada», the gruop’s senior member. Just like Zurich Dada, this Berlin-based DADA would be pretty shortlived. The first International DADA Art Fair, held in 1920, already sounded the death knell for a movement whose individual advocates would never yield to the humility of the collective group. Hausmann duly joined Kurt Schwitters, the sole member of a DADA group set up in Hanover in 1920 (after having unsuccessfully applied to the Berlin committee), while another group came to the fore in Cologne, led by Max Ernst and Johannes Baargeld. Dubbed since 1918 by Jean Arp, the group turned out to be no less ephemeral, because it collapsed in 1921. Its brief period of provocative, bothersome, creative activity was a flamboyant one, staked out by many a magazine. Among them, Die Schammade proclaimed by way of the subtitle: «Dilettantes, rise up!». Its members gradually joined the Parisian movement spawned by the magazine Littérature, created in 1919 as a brainchild of André Breton, who gathered the writers Louis Aragon and Philippe Soupault around him.

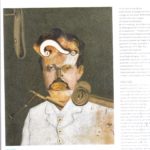

In 1920, Tristan Tzara finally reached the French capital and launched a new manifesto. All the leading artistic figures of the various «DADAS» came together, from Francis Picabia in 1919 to Jean Arp in 1920, followed by Man Ray in 1921, accompained by Marcel Duchamp, and lastly Max Ernst in 1922. But the euphoria did not last long. On the other side of the Atlantic, New York DADA has a slightly aloof place on this checkerboard. The city, which had remained neutral until 1917, the year when the United States officially went to war, attracted many artists from war-torn countries. The geographical distance made the war somewhat abstract and in the works produced by Francis Picabia, Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray there was no the same desperate urgency «driven» by the atrocities of war. New York DADA (which did not bear any such name until 1920) was much more freewheeling and gratuitous.

In 1920, Tristan Tzara finally reached the French capital and launched a new manifesto. All the leading artistic figures of the various «DADAS» came together, from Francis Picabia in 1919 to Jean Arp in 1920, followed by Man Ray in 1921, accompained by Marcel Duchamp, and lastly Max Ernst in 1922. But the euphoria did not last long. On the other side of the Atlantic, New York DADA has a slightly aloof place on this checkerboard. The city, which had remained neutral until 1917, the year when the United States officially went to war, attracted many artists from war-torn countries. The geographical distance made the war somewhat abstract and in the works produced by Francis Picabia, Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray there was no the same desperate urgency «driven» by the atrocities of war. New York DADA (which did not bear any such name until 1920) was much more freewheeling and gratuitous.

Though it certainly did not lack wit, it was schoolboyish, with plenty of sexual connotation, and created just as much scandal in that American city which had only become acquainted with modern art since the major Armory Show in 1913, where Cubism and other artistic innovations had been revealed to some 75000 visitors.

Though it certainly did not lack wit, it was schoolboyish, with plenty of sexual connotation, and created just as much scandal in that American city which had only become acquainted with modern art since the major Armory Show in 1913, where Cubism and other artistic innovations had been revealed to some 75000 visitors.

The versatile, loose, light-hearted group took wing in 1916, and fizzled in 1921, when Duchamp and Man Ray returned to Paris. DADA was an internationalizing virus in a divided world: it cropped up, if very briefly, in Italy, Barcelona, South America, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Belgium, and even Japan. The spirit of contradiction, revolt and insubordination had no nationality and, without any confining programme or insistent artistic dogma, DADA occupied a worldwide stage in a more or less natural way, in all its eccentricity.